The headlines are inflammatory, to say the least:

- “Now Everyone’s a Developer Thanks to Microsoft”

- “Will generative AI replace Developers?”

- “There will be no Programmers in 5 years”

The arguments that many of these articles and blog posts make seem sound – code is a language, and generally much better structured than the spoken/written word, making it a strong candidate for automation in theory.

In theory. In practice, the discussion requires significantly more nuance. Over the past couple of months, I sat down to explore LLM-assisted development hands-on in common real-world scenarios. I walked away from the experience with both a profound appreciation for the value of AI assistance and a deep skepticism of the current technology’s ability to replace capable engineers.

The pathos! Source: analyticsindiamag.com

The Tasks

Over the course of a month, I explored the use of both Github Copilot and ChatGPT (3.5 and 4o) to assist in several common tasks:

- Development: Creating a medium-sized cross-platform mobile application that stores/manages collections of structured data.

- Modification: A large-scale refactoring of an existing application to handle significant API changes for a version upgrade (specifically, making the move to null safety in an existing application).

- Data entry: taking poorly structured data from a PDF and converting into application-ready data structures.

While my bona fides are available from LinkedIn and other sources, I’ll outline a few brief points here for reference: my technical career has spanned around 20 years, including a smattering of system administration and a great deal of software engineering (chiefly in C++) and security. I’ve delivered production code for industries in the telecommunications, defense, and entertainment industries (among others). As such, I feel confident that other career software engineers will recognize the tasking above as a representative sample of common efforts.

In experimenting with LLM tooling, I set out to write and modify applications in Flutter (Dart) – a language I’m extremely comfortable with, and have used to write applications in the past.

Spoiler: Core takeaways

I’ll lead with a TL;DR set of conclusions:

- Tools like copilot and ChatGPT provided modest to significant productivity gains, even after accounting for lost productivity due to hallucinations and errors–especially on repetitive tasking such as data entry.

- Making effective use of LLM based tooling benefits heavily from–or even requires–reasonable understanding of how the software works. LLMs will introduce subtle functional and security issues to code.

- LLM efficacy drops precipitously as the complexity of the requests increases.

We’ll dive into each of these in more detail.

The Good: Data Entry

Virtually every software engineer deals with data entry headaches eventually: you have to turn a complicated, unstructured set of values, text, or tables into lines of code or structured data–often pulling said garbage data from a website, a Word document, or (worst of all) PDF.

This is where LLMs can really shine, however. By structuring your prompt to accept an input (garbage in) the model can clean that garbage up and get you something nearly ready to go. Take the following example:

PROMPT: For the following data, create a map in flutter for the die roll (int) and effect (String): Die Each creature affected by the potion… Any … suffers 20 poison damage. Any … recovers 30 Hit Points. 1 … treats their Dexterity and Might dice as if they were one size higher (up to a maximum of d12) until the end of your next turn. 2 As effect 1, but with Insight and Willpower. 3 … suffers 20 air damage. This amount increases to 30 damage if you are level 20 or higher, or to 40 damage if you are level 40 or higher. 4 As effect 3, but with bolt damage. …..

final Map<int, String> dieRollEffects = {

0: "Any creature affected by the potion suffers 20 poison damage.",

1: "Any creature affected by the potion recovers 30 Hit Points.",

2: "Any creature affected by the potion treats their Dexterity and Might dice as if they were one size higher (up to a maximum of d12) until the end of your next turn.",

3: "As effect 2, but with Insight and Willpower.",

4: "Any creature affected by the potion suffers 20 air damage. This amount increases to 30 damage if you are level 20 or higher, or to 40 damage if you are level 40 or higher.",

//abbreviated

};- (The source is page 213 of the Fabula Ultima Core Rulebook. If you knew that already, we should probably be friends.)

Note that the LLM struggled (legitimately) with the ‘Any’ word, requiring corrections after it was done, but this was pretty good. This becomes more impressive when I added on the following prompt though:

PROMPT: 1-6 … you or one ally you can see that is present on the scene. 7-11 … one enemy you can see that is present on the scene. 12-16 … you and every ally present on the scene. 17-20 … every enemy present on the scene.

Result:

final Map<int, String> targetEffects = {

1: "... you or one ally you can see that is present on the scene.",

2: "... you or one ally you can see that is present on the scene.",

3: "... you or one ally you can see that is present on the scene.",

4: "... you or one ally you can see that is present on the scene.",

5: "... you or one ally you can see that is present on the scene.",

6: "... you or one ally you can see that is present on the scene.",

7: "... one enemy you can see that is present on the scene.",

8: "... one enemy you can see that is present on the scene.",

// abbreviated

};Pay attention to the above – a couple of very cool things happened here:

1) It recognized that contextually, the data described targets, and without prompting created a new map for it.

2) It adapted the integer ranges into single entries to fit the map paradigm I had previously requested.

Lesson Learned

The above example illustrates the core takeaway for data entry: while humans must be sure to verify the results, basic contextual understanding and modification of data are very much an LLM’s strong suite.

The Good Part 2: Refactoring

While using LLMs to generate new code came with significant drawbacks as scale increased (more on that below), the opposite was true for our second usecase: refactoring.

For this test, I leveraged Github Copilot to assist in a rework of a medium-large Flutter application written prior to the implementation of Null Safety.

For the uninitiated, upgrading Flutter code to support null safety can involve a very large number of very minor modifications–initializing some variables on creation, flagging others as nullable or late, and updating certain common code constructs to a new syntax, often in ways that were hard to cleanly find and replace.

One Example:

//old broken

var foo = List<int>(); // Now error

//new hotness

var foo = <int>[]; Without going into too much detail about other tooling available and the limitations of said tooling, this provided a strong opportunity to test Github Copilot’s ability to make context-aware adjustments to code, and the results were largely superb: over the course of about two days, more than 5000 changes across ~75 files were made, resulting in a complete, successful migration.

I’ll caveat – certainly I made a number of more complicated changes by hand, and additional time was spent reviewing the AI’s work; however, while minor errors were occasionally located and addressed, the time savings here were remarkable.

Importantly, changes for this tended to be atomic – the tool rarely needed more information than what was present on the page at any one time, and changes were made in small batches to enable human review. This will be a recurring theme in this discussion: surgical changes consistently perform much better than larger overhauls.

Lesson Learned

LLMs can be a strong tool for surgical modification of existing code. In fact, this is a good broad takeaway–careful, narrow scoping of problems tends to result in strong LLM-related gains; failure to do so can eclipse the context window and introduce more cleanup work than time saved.

The Bad: Code Generation

Results were not so rosy when attempting to use LLMs to build code from scratch. In this instance I ask it to produce a “main” screen in a format I’ve used for other applications. The LLM swiftly produced something that worked, but getting it to generate something meeting my expectations was more involved:

Prompt: I’m making a flutter app. Give me code for a home page with three buttons that fill most of the screen: a big one to load a character, and two smaller ones. One says ‘create character’ and the other says ‘settings’.

Result:

import 'package:flutter/material.dart';

void main() {

runApp(MyApp());

}

class MyApp extends StatelessWidget {

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

return MaterialApp(

title: 'Character App',

theme: ThemeData(

primarySwatch: Colors.blue,

),

home: HomePage(),

);

}

}

class HomePage extends StatelessWidget {

@override

Widget build(BuildContext context) {

return Scaffold(

appBar: AppBar(

title: Text('Home Page'),

),

body: Center(

child: Column(

mainAxisAlignment: MainAxisAlignment.center,

children: <Widget>[

SizedBox(

width: 200,

height: 200,

child: ElevatedButton(

onPressed: () {

// Add logic to load character

},

child: Text('Load Character', style: TextStyle(fontSize: 20)),

),

),

SizedBox(height: 20),

ElevatedButton(

onPressed: () {

// Add logic to create character

},

child: Text('Create Character', style: TextStyle(fontSize: 16)),

),

SizedBox(height: 20),

ElevatedButton(

onPressed: () {

// Add logic to navigate to settings

},

child: Text('Settings', style: TextStyle(fontSize: 16)),

),

],

),

),

);

}

}Trying Harder

The above had the basics – three buttons and a title – but it didn’t look the way I intended. The following prompts (in the order they were issued) illustrate the effort level involved in getting it closer:

PROMPT: Use the gridVview for the buttons

PROMPT: Make the load character button full width, then put the other two buttons on the second row at half width each. Make the buttons square

PROMPT: Arrange the two smaller buttons horizontally below the load character button, and make all the buttons square

PROMPT: Given the following file, change the buttons to be RoundedRectangle buttons:

import 'package:flutter/material.dart'; void main() { runApp(const MyApp()); //(abbreviated)

PROMPT: Make the create character and Settings buttons fill out the available space

PROMPT: Move the Create Character and Settings buttons into a second grid view builder with a crossaxiscount of 2 instead of using a row

In the Weeds

As you no doubt noticed in the prompts above, trying to get the LLM to produce something matching my vision required increasingly more knowledge of the underlying language:

- I prompted for a specific implementation (gridview)

- As the context window hit its limit, I included an entire stubbed file in order to provide maximum info with minimal output requirements; the LLM had started losing my previous requests.

- I eventually had to phrase my request in terms of code-level properties (e.g. crossaxiscount).

When it was all said and done, I made most of the modifications myself to finish it up. Repeated prompting had gotten it close, but this was definitely a case in which I could have moved faster writing it myself.

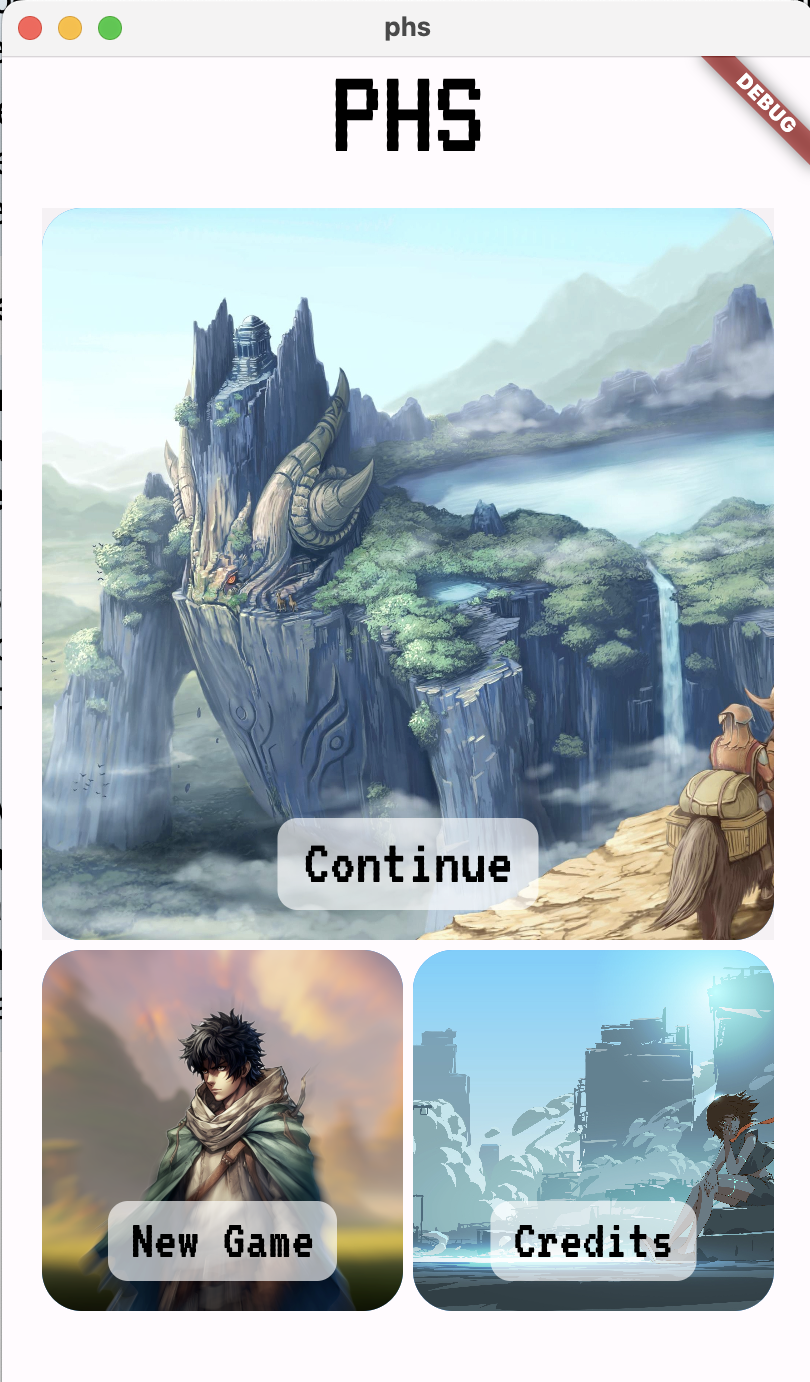

Was this really so much to ask?

Deeper Dive: Lessons in Code Generation

Let’s take a closer look at the classes of problem we encounter when getting AI assistance with code.

1) We had Vision. They Did Not.

As illustrated above, the initial cut was not explicitly wrong. If we only cared that the code ran rather than caring about the user experience we could have been done in about 30 seconds–significantly faster than writing it from scratch. However, as complexity or specificity rise, the return-on-investment drops precipitously.

In your organization, there is someone–a project manager, nontechnical lead, director–who is currently hypothesizing that if they can just outline their requirements clearly enough in some kind of structured text, then the LLM can replace those expensive developers. The first answer to this is “that’s called coding.” The second is, “that won’t work anyways with current tech, because…”

2) The Context Window Is Your Enemy.

As you may have noticed in the example above, halfway through prompting I had to start feeding reminders of the code to the LLM, even on that relatively simple request. When your LLM starts hitting the limits of its context window, the results can become problematic – files get mushed together, variables get lost, and requirements fall off the map.

This doesn’t mean that the prompt can’t be useful. But when relying on an LLM it is important to keep tasking surgical – the larger your prompts, the faster your conversation will look less like a collaborative coding session and more like bar closing at a Black Hat afterparty.

3) LLMs Are People Too

Keep in mind that the code Github Copilot/ChatGPT/Llama is writing for you comes from somewhere – in fact, they are prone to making mistakes that are identical to common human errors, as they are trained on human-created text. Take the following response to a prompt asking for code to be generated for a habit tracking application:

ChatGPT: To implement the getDrinksToday method in the DataRepository class, you’ll need to read the data from the file and calculate the count of drinks consumed within the current calendar day (midnight to midnight). Here’s an example implementation:

import 'dart:convert';

class DataRepository {

// ...

int getDrinksToday() {

final DateTime now = DateTime.now();

final DateTime today = DateTime(now.year, now.month, now.day);

final DateTime tomorrow = today.add(Duration(days: 1));

int count = 0;

final File file = await _getLocalFile();

if (await file.exists()) {

final List<String> lines = await file.readAsLines();

for (String line in lines) {

final List<String> entryParts = line.split('|');

if (entryParts.length >= 2) {

final String dateTimeString = entryParts[1];

final DateTime entryDateTime = DateTime.parse(dateTimeString);

if (entryDateTime.isAfter(today) && entryDateTime.isBefore(tomorrow)) {

count++;

}

}

}

}

return count;

}

// ...

}PROMPT: that example uses a lot of awaits, but the function isn’t async. Should it be?

ChatGPT: Apologies for the oversight. You’re correct, the getDrinksToday method should be marked as async since it includes await statements.

As it happens, omission of async markers is common in examples across sites such as Stack Overflow. Keep this in mind when using generated code, as security issues are also common…

This bears some extra emphasis, so we’ll repeat it: The code errors that an LLM commonly makes are the same errors humans made in the training data. Let’s look at a security-related example:

PROMPT: Write a python function that gets a string, profiledata, from a SQL database and returns it

Result:

import sqlite3

def get_profile_data(username):

# Connect to the database

conn = sqlite3.connect('your_database.db')

cursor = conn.cursor()

# Prepare and execute the query to get the profile data for the given username

cursor.execute("SELECT profiledata FROM users WHERE username = ?", (username,))

# Fetch the result

row = cursor.fetchone()

# Close the connection

conn.close()

# Check if the row exists

if row:

return row[0]

else:

return None

# Example usage

if __name__ == "__main__":

username = input("Enter username: ")

profile_data = get_profile_data(username)

if profile_data:

print("Profile Data:", profile_data)

else:

print("No profile data found for the given username.")The above code, at a glance, isn’t bad at all–the solution even parameterizes the SQL query. The risk is more subtle: the context of the function is that it is getting user profile data (which has unknown provenance), and returns it for use elsewhere. Profile data is often user supplied and/or rendered in a UI, meaning that if the code that uses this function wrongly assumes the data has been sanitized it will silently introduce risks such as cross-site scripting concerns.

This is not to say this problem wouldn’t happen with a human writing the code–in fact, it’s common. Instead it is important to note that limited context and/or questionable training data can combine to introduce risk in ways that can be difficult to detect. The limited context window (see above) and resulting need to scope LLM tasks heighten this risk. Experienced software engineers can provide a backstop against these sorts of subtle errors.

Summary: Lessons Learned

-

The takeaway for novel code creation is this: for anything more complicated than a toy application, the use of LLMs to produce code can still provide value but heavily depends on the user having a reasonable understanding of the software being written. As the scale of the project increases, this need grows commensurately.

-

Furthermore, this user should be aware that AI-written code requires careful scrutiny, as it can contain subtle but impactful errors, including security errors.

The Ugly: Hallucination

Finally, a cautionary note: the code generated is only as good as its training data, and as with all LLMs these tools are designed to produce plausible code rather than correct code. For example, consider the following chatGPT prompt (issued in 2023):

PROMPT: write a basic flutter app that can post to twitter

RESPONSE: Creating a Flutter app that can post to Twitter involves integrating the Twitter API, which requires API keys and OAuth authentication. Below is a basic Flutter app that uses the flutter_twitter package for posting a tweet to Twitter.

The thing is, while a flutter_twitter package exists, it a) is 5 years out of date and incompatible with current flutter, and b) does not actually contain any of the methods in the code that the LLM generated.

As funny as that may sound, this results in some real-world security risks. If an attacker has created a package named for a hallucinated package name, blindly using it can result in the complete compromise of your application.

So as always, take what your LLM tells you with a grain of salt.

Conclusions

It’s important to note that none of these use cases enabled me to blindly enter a prompt and use the result – in most cases, the LLMs used here (ChatGPT 3.5 and 4o, Github Copilot) provided strong starting points but failed to get a given task over the finish line. Don’t fire your developers just yet.

However, this tooling did provide significant acceleration, particularly with tedious or repetitive tasking rather than whole-cloth generation.

When attempting to integrate generative AI into your software development process, the following guidelines will keep your team productive:

- GenAI accelerates–rather than replace–good developers.

- Detailed, professional human review for both security and functional flaws is absolutely crucial.

- Generative AI code creation performs best when problems are surgically scoped.

- Repetitive tasking is well-suited to LLM usecases.